- After Robyn was promoted to an officer, she soon realised how important women were to the Australian army

- On peacekeeping missions, local women felt safe enough to confide in Robyn so she could help implement important changes in their lives

- Later she became one of the first ever women to ever take the Commando selection course and later became the first woman to earn the coveted green beret

- But when she retired after 22 years of service, she struggled with chronic pain and it was taking a toll on her mental health

- Robyn Fellowes, from Ravensbourne, Qld, shares how she saved her own life when she was just seconds from death…

Sweat poured down my forehead as I lifted the heavy stretcher.

I can do this, I told myself.

It was 1999, and I was part-way through the commando selection course.

Thankfully, the ‘body’ we were carrying was actually a heavy sandbag, but everything else about the arduous 30km march was as tough as real-life conditions could get.

Growing up, I’d had it tough.

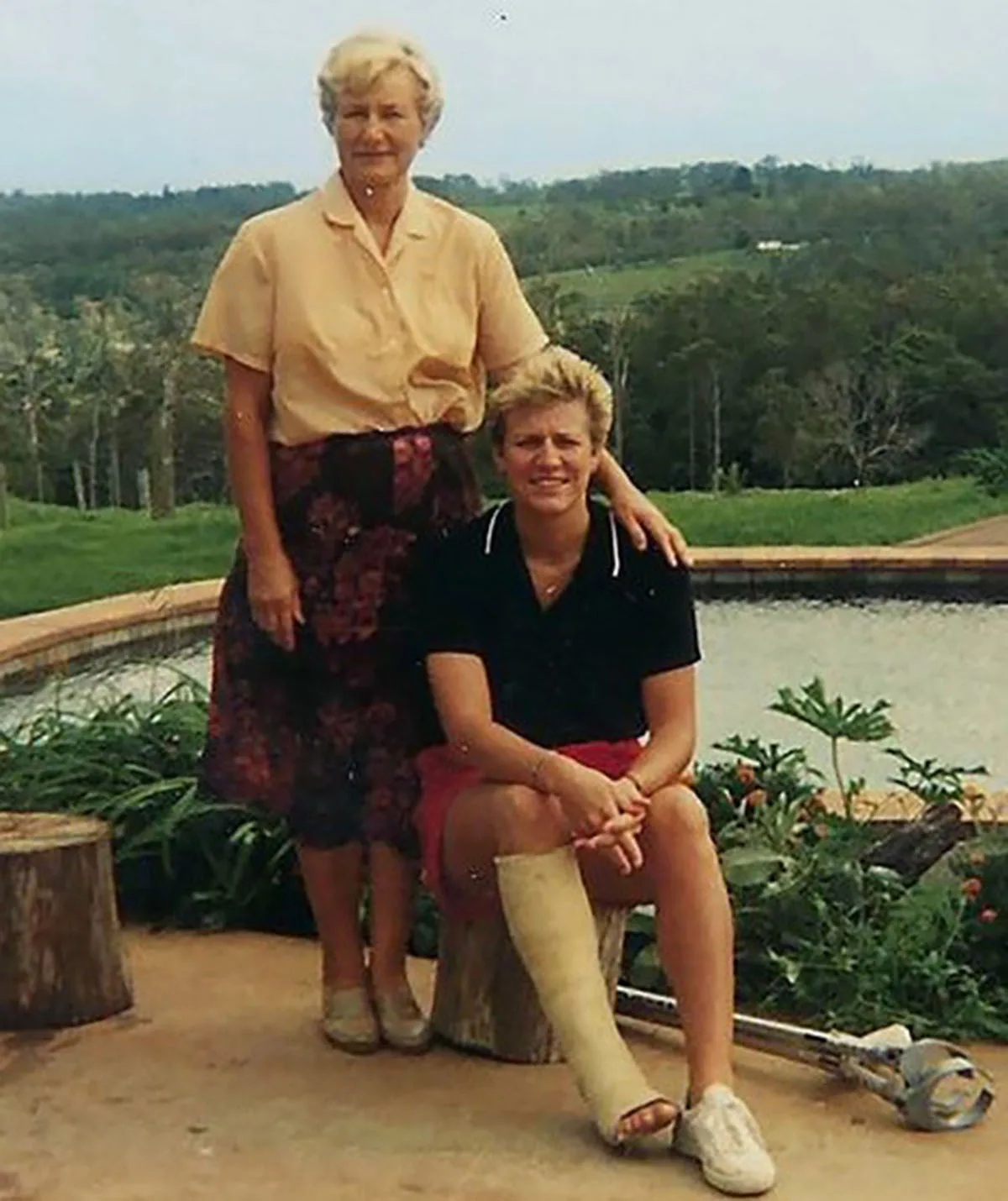

My dad, Michael, had been violent, often beating my mum, Helene in front of me and my three sisters.

Although Mum was frightened she remained strong for us.

“Why don’t we just leave?” I begged her one day.

“Because he’ll find us and kill me,” she replied.

I never asked again.

Mum used us kids as peacekeepers, asking us to help get Dad in a good mood.

I did that by excelling in athletics at school and on a national level.

Seeing me win medals was one of the only things that made Dad happy.

When I was 17, I joined the army, knowing my fitness would stand me in good stead as a soldier, especially as one of very few women.

Within 18 months I’d been promoted to an officer and within a few years, I was sent on my first overseas deployment to Bougainville, Papa New Guinea.

There, I realised how important women were to the army.

While local male leaders and chiefs insisted the peacekeeping mission was going great, local women, who felt comfortable confiding in me, disclosed that they were actually terrified of the machete-wielding gangs, and many of them had been raped.

“What can I do to help?” I asked.

“If we can get together safely with other women on the island, we could discuss how to fix the security situation,” one responded.

Because I was a woman, they trusted me, and I did my best to help facilitate their gathering so they could create their own solutions.

The following year, I was asked to be one of the first women to ever take the commando selection course.

Seeing the necessity of women to the special forces, I accepted the challenge immediately.

Commandos make up the special forces but before 1999, women weren’t allowed to become one.

Now, as a one-off experiment, three women were invited to take the test.

I suspected no one in the military actually expected us to pass, they just wanted to show they’d given us a chance. That only made me more determined to succeed.

Now, marching through the heat, the weight of the stretcher dragging me down – I knew the men were finding it every bit as tough as I was.

We were hungry and sleep deprived for 19 days – to see how well we performed under pressure.

To my delight, I passed and was the only woman to partake in commando courses like parachuting, close quarter battles and tactical small boat training.

After a year, I became the first woman to earn the coveted green beret.

“You’re officially a commando,” my commander announced.

I worked in special ops at the headquarters until 2006, when I was deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan.

Again, my skills as a woman were crucial to cultural issues faced by female civilians and soldiers.

For example, men often dressed in burkas to pass security points, relying on the fact that male soldiers weren’t allowed to check women.

But a female at the checkpoint could search anyone, busting those trying to sneak through.

It wasn’t all peacekeeping work though.

Many times I feared for my life when we were ambushed and had to escape explosions and gunfire.

Over CCTV, I witnessed a man shooting a woman in the head – I was devastated and determined to help save vulnerable women like her.

In 2009, aged 39, I retired after 22 years of service.

Although I loved my job, I struggled with chronic pain and needed to slow down.

I moved back to Toowoomba, Qld, and set up a personal training business.

Unbeknownst to me, the trauma I’d experienced in my life was starting to take its toll on my mental health.

One night I was driving home when I saw a huge gum tree in front of me.

Maybe I should drive into it, I thought out of the blue, and make my pain go away.

I began to steer towards it, maintaining speed.

Then, with a sudden flash of clarity, I quickly yanked the wheel towards the road again.

I made it home safely but I’d really scared myself.

My life needs to change, I decided.

I hired a business manager, reduced my hours, started physio for my pain, and made more time for family and friends.

For the first time, I was finally at peace.

In 2014, thanks to Prime Minister Julia Guillard, all combat roles were opened up to women.

Finally, I thought.

By 2015, I was eager to help people again.

Almost like magic, I got a call asking me to go back to Afghanistan as a reserve.

Being back in uniform felt great.

This time I was focusing on recruitment and retention of women in the Afghan National Army.

The leaders were finally listening – women need to be involved in the security of their own countries.

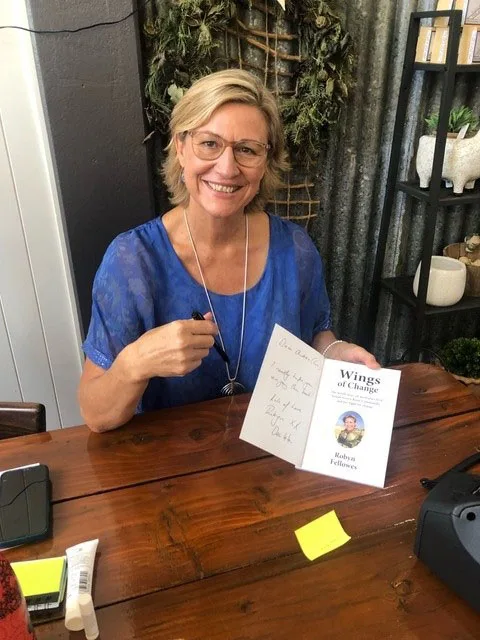

Once I returned home, I took a year off to write about my military experiences in my memoir, Wings of Change, and I’m so proud of it.

I hope it inspires readers to know they can overcome any adversity by making change.

I might be a green beret but I know if I can do it, you can too.

Wings of Change is available in print, e-book and audiobook.

For support, call Lifeline for free 24/7 on 13 11 14 (Aus) or 0800 543 354 (NZ)